Gender-based violence is a pervasive issue that often goes unrecognised and unchecked. We all know it exists, but our understanding of it can be quite limited in scope and type.

In discussions about violence, emphasis is generally put on direct violence which includes physical acts like hitting and pushing, with little focus on forms of violence that are just as damaging. Direct violence also includes sexual violence, from harassment to rape, and less frequently discussed acts like human trafficking, exploitation of domestic workers and online harassment.

We have fallen into the habit of excusing direct violence. We find ways to put blame on the survivors and victims of violence. This is sometimes because we want to protect the abusers, but in most cases, we fail to recognise certain acts as violence. We use words like “teasing” and “flirting” to downplay harassment, refusing to see the distinction between them.

Women and girls are seen as unfriendly or “stuck up” when they dare to say or show that attention is unwanted. Men and boys are allowed to make nuisances of themselves because there is more value on their performance of masculinity and seeking to fill their own needs than the comfort and safety of women and girls.

Far too many people concern themselves with what a women or girl was wearing, where she was, who she was with and why she was there with whomever was in her company when she reports sexual assault. This refusal to recognise the violation in favour of misplacing blame for the violation is another act of violence.

Indirect violence includes systemic issues and the stereotypes with which we are familiar, even if we do not recognise them as such.

Yesterday, in a session focused on the United Nations Convention for the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women, a differently-abled woman spoke out about the lack of access to spaces — public and otherwise — and increased vulnerability of differently-abled women.

She identified the exclusion of differently-abled women as an act violence. This is a form of violence we do not often recognise or acknowledge, but is part of the lived reality of differently-abled people and compounds the marginalisation of differently-abled women. Women do not get to be only women. We are women and black, women and queer, women and poor, women and elderly and any number of other layered identities.

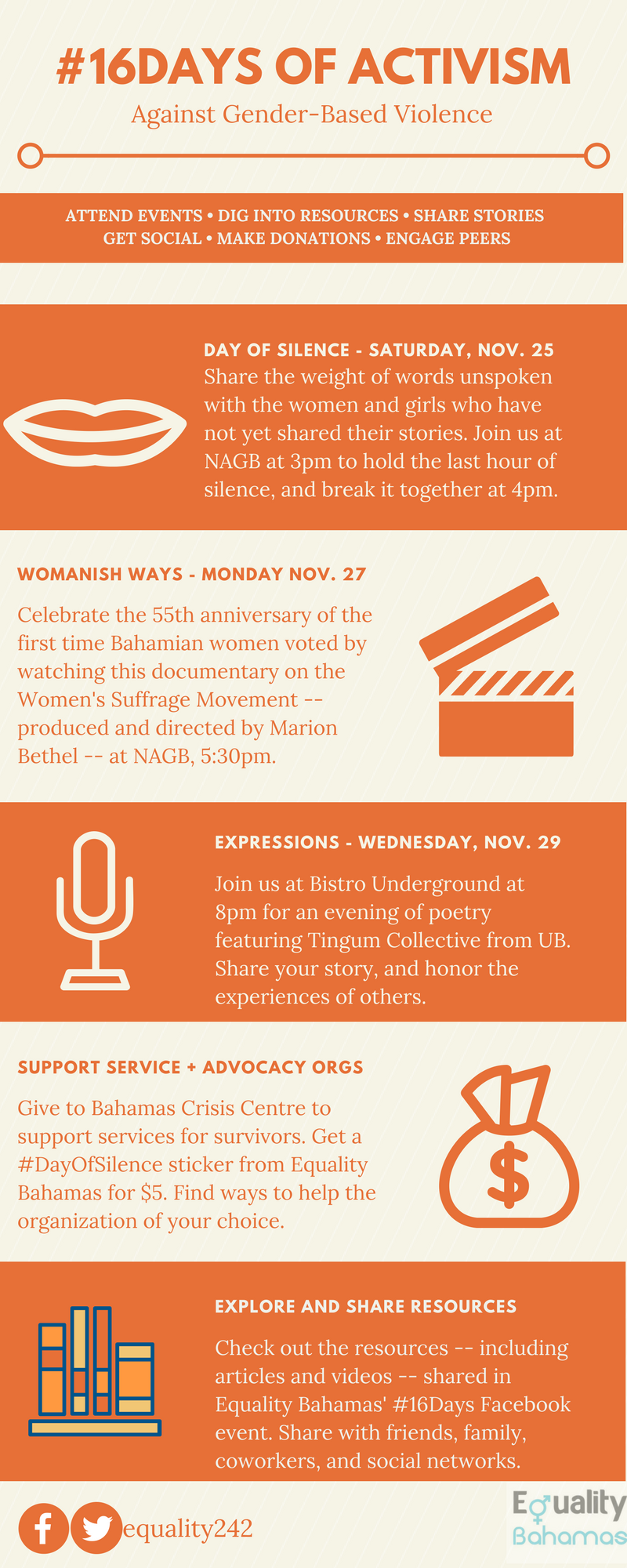

Every year, 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence — a global campaign — run from November 25 to December 10. It opens on the Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and closes on International Human Rights Day. These observations underscore both the pervasive and possibly most easily identified forms of gender inequality and the recognition of women’s rights as human rights. This campaign coincides with National Women’s Week in The Bahamas which this year began on the fifty-fifth anniversary of the first time Bahamian women voted.

The Department of Gender and Family Affairs planned Orange Day, a church service and the information and walk-through of the CEDAW report. The Department also disseminated information on NGO-led events and initiatives, including the Zonta Says No town hall held last night and the series of events and actions organised by Equality Bahamas.

These included a Day of Silence, screening of Marion Bethel’s Womanish Ways — a documentary on the Bahamian Women’s Suffrage Movement — and open mic at Expressions at Bistro Underground being held tonight, featuring Tingum Collective from University of The Bahamas, Blue Elite dance troupe and poets Zemi Holland and Letitia Pratt.

This 16-day campaign includes a broad range of activities which are aimed at raising awareness and driving action. Beyond wearing orange and attending events in droves, it is critical we advocate for the change we need, systemically, to end gender-based violence. As Donna Nicolls, of Bahamas Women’s Watch, stated at a few events thus far during the campaign, we need to continue our action and remember that 16 days is not enough.

The campaign is beneficial for introducing people to the issues, increasing and deepening understanding of those issues and connecting with organisations and individuals working on women’s rights and ending gender-based violence year-round all over the world.

Last year, the Life in Leggings movement started in Barbados, swept across the region and encouraged many Bahamian women to share their stories of sexual violence. For most of them, it was the first time they had spoken about their experiences.

While the campaign was not launched as a part of the 16-day campaign, it connected thousands of Caribbean women and highlighted the similarity of stories, laws and systemic issues. This year, just before the beginning of the campaign, people in Guyana stood in support of high school girls who reported sexual violence by a teacher and rebuked the headmistress who shamed girl students for not supporting their teacher. They pushed for a response from the Ministry of Education with regard to the teacher and the headmistress. It is clear none of us can wait for annual campaigns, nor can we limit our advocacy and activism to these limited periods.

Everyone is not able to participate in global campaigns or contribute to ongoing work in the same ways, so it is important to consider various levels of involvement, time commitment, and frequency of activity. As the holidays approach and the season of giving makes us more willing to part with money, think about how can you support an organisation advocating for the rights of women or providing support to women and girl survivors of violence.

While money is always helpful, a phone call or email to find out about items needed is always welcome. The Bahamas Crisis Centre, for example, is currently in need of nonperishable food including noodles, tuna, corned beef and small packs of rice.

Whether you can give a can of tuna or a case of tuna, it would be appreciated by both the organisation and its clients.

There are always people who want to help, but are not able to give tangible items, and there is space for them too. Bahamas Sexual Health and Rights Association (BaSHRA) is running Baby Can Wait — a comprehensive sexual education program — in a few high schools this academic year and could certainly benefit from more volunteers willing to be trained and assigned a class to teach for one hour per week for ten weeks. There are many ways to take action and Equality Bahamas is sharing a new idea every day during 16-days.

The first step is to think about violence in its various forms, where it shows up in your life and how you respond to it. Every act of violence is not intentional, but is still wrong, so it is on the individual, along with organisations, to be intentional in our actions and inclusion of women and girls and all other marginalised people.

Published in Culture Clash — a weekly column in The Tribune — on November 30, 2017

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!